A Story From the Old Country

Brian Leyden

On St. Patrick’s Day, with a clump of shamrock in his buttonhole and a couple of pints of stout under his belt, my father announced in the bar: “This year, I’m going to the mountain to cut turf.” The other drinkers roared laughing.

On St. Patrick’s Day, with a clump of shamrock in his buttonhole and a couple of pints of stout under his belt, my father announced in the bar: “This year, I’m going to the mountain to cut turf.” The other drinkers roared laughing.

If he had been living in Galway or Mayo or the wilds of West Kerry his decision to harvest fuel for the fire from the mountain might have been greeted with greater solemnity. But why would any man living in the coal mining village of Arigna in North Roscommon want to cut turf? The sweet unmistakeable smell of turf smoke in the air might be a feature of rural life in the West of Ireland at that time, but not in Arigna. In its place we had the thick smog and sulphur reek of native coal fires. In Arigna coal was King.

“Have you rights?” someone asked.

“Who’s bothered any more about rights on the mountain?” my father said. “I’ll cut turf on the first bank I come to.”

A discussion started amongst the coal-miners about the great men going long ago, and the amount of turf they could save in one day; men who could blacken the mountain with turf. But that generation was dead and buried, and it was doubtful if there was even a proper turf cutting sleán left in the village? Might a garden spade or a hay knife be used instead to strip a turf bank? There was general agreement that cutting turf in neat level benches, or ‘spits’, was an art in itself. And you had to take into account the quality of the turf on different parts of the mountain. Sitting on high stools around the bar, the coal-miners saved so much turf in theory that the bar tender, Mick Flynn, finally said: “Someone open the back door or this turf will never dry.”

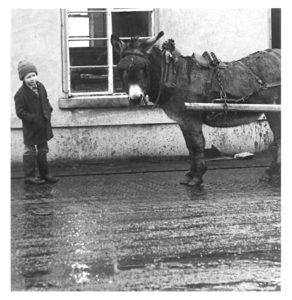

In early May, straight after the dinner – a midday affair in our house – we tackled the ass and cart, the ass being an all-purpose hairy engine more suited to mountain terrain than the grey Ferguson TVO tractor. We left the surfaced road and turned up the steep incline of the bog lane. A loud fart came from the ass when the strain came on the tackle: “He’s switching over to the diesel tank,” my father said.

After the pasture fields bordered with green and gold flowering gorse, we met rock and heather and drifts of lovely white bog cotton. A mountain hare ran a wide circle along the horizon, then took a sideways leap onto a new course to make a fool out of our dog Sally, who returned panting, happy like us to be on the mountain for sport more than any reward.

We were amazed when we spotted a neighbour preparing a turf-bank further on. He had rushed his dinner and reached the mountain ahead of us. With his jacket off, he laid claim to the first turf-bank beside the bog lane. Two days later the place would be fenced off more securely than Fort Knox.

We continued as far as Noone’s worked-out mineshaft, where the coal and slate coloured lane ended.

“Go back…go back… go back,” a disgruntled red grouse squawked as it broke cover and flew from the turf-bank that we decided on. Unloading the tools and tea-making things, we then heeled-up the cart and tethered the ass on a long rope. My father lit a Woodbine, using the match to burn off the old heather. Smoke drifted towards the sky like a rebel uprising. When he finished his cigarette he cut the first layer of poor, wiggy turf. The second spit was better; good black turf that my father said would dry as hard as a goat’s knee. He cut into the turf-bank in benches and each slice of the sleán scored the soapy black peat in a hound’s-tooth pattern. I had the job of barrowing away the buttery new sods for scattering.

We were working for about an hour when Tommy Tivnan arrived in a spruce white shirt, a sleán across his shoulder, whistling the first bars of “When I first said I loved only you, Maggie.” He gave us a cheery wave and set to work on the opposite turf-bank.

Johnny Guihen was the next man to arrive. He was a coal-miner who grazed his cattle on the mountain for the summer between Rockhill pit at one end and Derrinavoggy pit at the other end. He counted his short-horn cattle in the morning and the evening on his walk to and from work and he pointed out to me the dangerous airshafts in-between, and warning me to keep clear.

When we got parched for tea, we found a forgotten clamp of turf and started a fire with twigs inside a ring of stones. We boiled water in a saucepan without a handle. Tommy Tivnan brought over his sandwiches. Tasting of turf-smoke, the tea was, as my father said, strong enough to trot a mouse on, but we ate with keen open-air appetites the soggy egg and tomato sandwiches seasoned with salt from a twist of newspaper. Then Bernie Gilhooley appeared, rolling up his sleeve and sticking his arm in the cold, mineral-dark waters of the bog hole to soothe the rheumatism caused by an old pit injury.

“Keep your head under for ten minutes, Bernie,” said Johnny, “that’ll cure all your aches and pains.”

Sitting down drinking his tea, my father got a midge in his eye.

“As small as you are and as big as the mountain,” he said, “and you had to fly into my eye.”

We nearly burned as much turf as we saved while the yarns were told around the fire and heroes were remembered: Lester Piggott – “If he was only riding a donkey, bet on him.” And Mohammed Ali – “Too bad, too fast and too beautiful.”

My father tossed the dregs from his cup and said there would have to be further trips to the mountain to finish the cutting and the scattering; to foot or ‘rickle’ the turf into little pyramids, crowned with a level sod along the top to keep off the rain; to gather the turf in clamps and to build the clamps into bigger reeks; to haul the turf home in loads using the ass and cart, with more loud reports from the ass going downhill when the strain came on the breeching.

After only half-a-day’s work, my arms, my legs and back ached and I felt daunted by the work that lay ahead. But I was young and would soon get my strength back.

My father, however, would have this cloudless summer on the mountain and then his lungs would progressively weaken – not from coal dust or silicosis or farmer’s lung, but from a lifetime of smoking; his movements gradually narrowing to gestures and finally a complete stop. He died sitting upright in his bed at home, missing the next breath of air.

But on that open day he sat hunkered before a turf-fire, happy to be sharing around cigarettes amongst men resolved to claim back an acre of mountain. Coal-miners with their best years over. Men whose work had kept them underground for so much of their lives, yet their faces raised now to catch the light and a sweet mountain breeze under a faultless blue sky where the larks sang their hearts out.

‘Turf Cutting Rights’ is an extract from Brian Leyden’s best selling memoir The Home Place. Available on Amazon. (info@lepusprint.com)